ZELDA’S LEGACY

On March 10, 1948, at 48, Zelda Fitzgerald, widow of F. Scott, died in a fire in a locked hospital room during the last of her many confinements for chronic mental illness. Variously diagnosed as schizophrenia and bi-polar disorder, at least one biographer asserts that a major objective of her treatment was to restore her to the appropriately domestic life she had rejected. Zelda was then merely one of innumerable women in history whose creative potential went unrealized or which had been subsumed by a prominent husband’s.

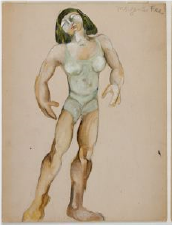

A ballet student in girlhood, at the too-late age of 27, Zelda made an obsessive try at a career as a dancer. She was a writer who published one poorly received novel, Save Me the Waltz (1932), and only after major revisions demanded by an infuriated F. Scott who had planned to use some of the same material in Tender is the Night, then a work in process. Zelda was also a capable artist who, besides her painting, like Hans Christian Anderson, found a métier in decoupage, creating cutout paper dolls which she believed had educational value and which she tried unsuccessfully to get Scott’s editor, the legendary Maxwell Perkins, to publish. The dolls, inspired by notable French painters, were exhibited in small venues and touted as a way to introduce children to contemporary art. Here’s Zelda’s portrayal of the sorceress “Morgan Le Fay” (c. 1941).  In Zelda’s imagining, the supernatural, sexually voracious Morgan is rendered so as to manifest her power in an unambiguously masculine body. A collection of her dolls was published in 2022 as The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald, by her granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan.

In Zelda’s imagining, the supernatural, sexually voracious Morgan is rendered so as to manifest her power in an unambiguously masculine body. A collection of her dolls was published in 2022 as The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald, by her granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan.

A tomboy as a child, and a jazz age flapper as a young woman, it is not difficult to imagine her behaviors as female emancipatory expressions. Zelda extolled the carefree, sexually open, rebellious life, declared she wished it for her daughter ahead of “a career that calls for hard work.” But Zelda’s industry and the intensity of her creative pursuits belie her praise of the lighthearted and superficial ethos of the day. At some level she recognized the truth observed by her biographer, Nancy Mitford: the life of a flapper was “potentially destructive and that it would demand its own continual and wearying performance.” Of course, in the end she opted, however conflictedly, for a domestic role alongside F. Scott.

Zelda’s resentment of her husband—if not his creativity then his dismissiveness of hers–was not well concealed. Save Me the Waltz is viewed today as a protest of female oppression, and Zelda, herself, as a feminist martyr. When given an opportunity by the New York Tribune to pen a light-hearted review of Scott’s The Beautiful and Damned, Zelda urged readers to buy the book for its aesthetics, which she attributed to “a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar.” She concluded: “Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

Not only did F. Scott not acknowledge the degree to which he purloined Zelda’s writings to enhance his own, but he shamelessly modeled his female protagonists after her, and in the least flattering way; they are all, like Zelda, beautiful seductive women from wealthy backgrounds who ultimately destroy the men they ensnare. Zelda seems to have taken her retribution in a way to inflict maximum wounding–by attacking his masculinity–likely his greatest vulnerability..

If his buddy, Ernest Hemingway, is to be believed, Scott confessed to him one night in a Paris brasserie that, “Zelda said that the way I was built I could never make any woman happy and that was what upset her originally. She said it was a matter of measurements. I have never felt the same since she said that and I have to know truly.” Hemingway, also not spared Zelda’s emasculating comments, was accused by her, according to Nancy Mitford, of being “just a pansy with hair on his chest.” (And one cannot ignore the homoeroticism in Hemingway’s taking Scott into the toilet for some dropped pants reassurance.)

Zelda’s legacy, apart from the pathos and passion of her life, and the era in which it was lived—all conjured up by the mere mention of her name–is her visual art. According to Laura Maria Somenzi, a Woodrow Wilson Undergraduate Fellow who curated a 2011 exhibition at the Johns Hopkins Evergreen Museum and Library, more than 100 of her works have survived, In an accompanying catalogue, Somenzi reports on Zelda’s studying Van Gogh and his influence on her own painting. In addition to spending time with the likes of Picasso and Leger, she took painting lessons, and was profoundly affected by Georgia O’Keefe, both as an artist and female.

One can perhaps detect some O’Keefe influence in this painting of a female figure with flowers, although the subject’s manly shoulders, and hypertrophied muscles are a distinctively Zelda touch.

Female figure with flowers (c.1932-34) Gouache and pencil on paper. Department of English, The Johns Hopkins University.

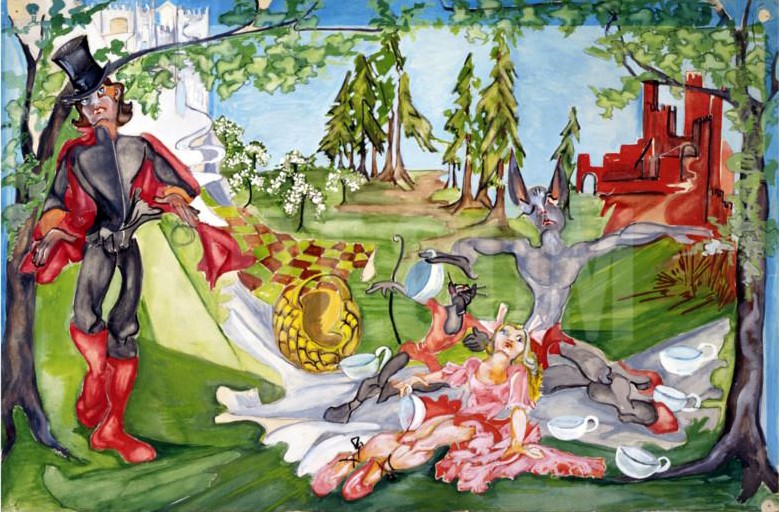

Contemporaneous with her final confinement at the Ashville, North Carolina, hospital she produced this disturbing surreal depiction of a picnic which can be read as a summary of her life:

Titled, “A Mad Tea Party,” (Gouache on paper, F. Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald Museum), it possesses none of the fun of Lewis Carroll’s absurdist vision, but projects a joylessness one cannot help but read into her psyche. The strewn teacups, like the basket, are empty, the figures on the blanket—a collapsed, white-faced, emotionless, frail, doll-like woman in ballet shoes, and an upright, gray, faceless, muscled, masculine form, also in ballet shoes—and overseeing it all, a top-hatted man in black formal wear with a red cape suggest the sense of failure, the emptiness and lack of control she must have felt at that low point in her life.