“Parasite” is not what you’re being told it is. A review with spoilers.

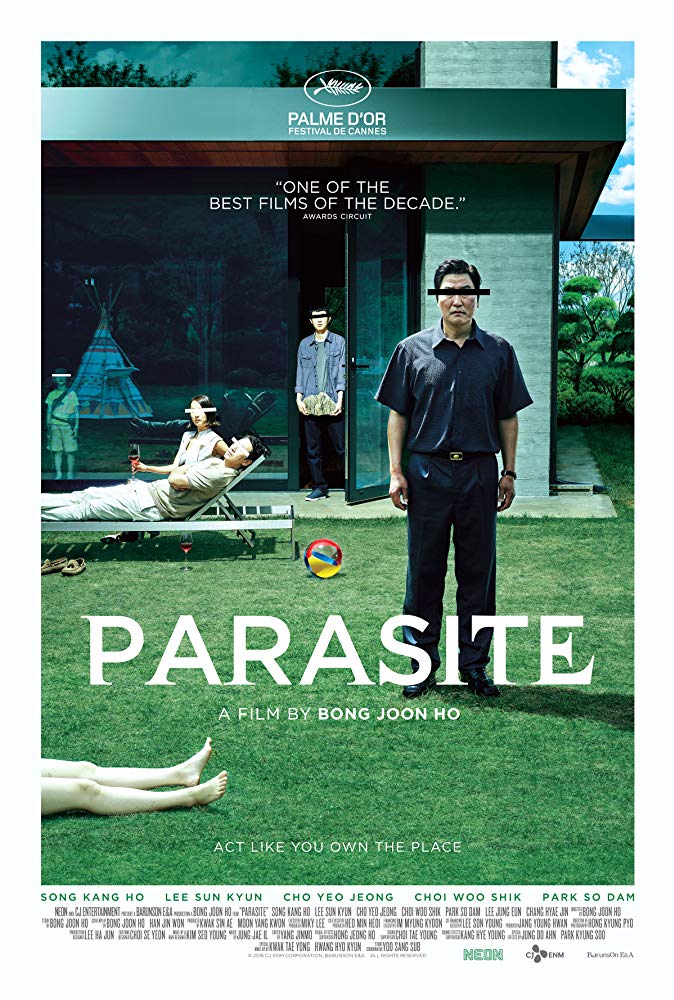

“Parasite” (Bong Joon-Ho 2019)

“Parasite” is not what you’re being told it is. A review with spoilers.

The New York Times this morning joins other media commentators in describing this movie as a “class-struggle thriller” and, in the same post-Oscar article, as a “comedy-thriller.”

These are misleading descriptives. Parasite is not about class struggle, although it ham-handedly depicts a poor and a nouveau-riche family. It is not a comedy, although it employs biting satire. It is not a thriller, although it appropriates and mashes up conventions of thriller, comedy, class- conscious, and even horror genres.

What Parasite is, is an entertaining, literary film about amoral characters in an amoral world, the characters existing not to provide an in-depth exploration of who they are but in the service of a barely credible plot, in a story that presents an amoral, rather nihilistic world view. Set in Korea’s highly stratified capitalist society, it does not argue for some Marxist revolution, nor is the underclass depicted as challenging capitalist success or exploitation, but simply wanting a piece of it. Indeed, its cleverly ambiguous title immediately provokes the question whether the poor or the rich family is the social parasite.

Bong presents us with the Kim and the Park families, the former poor, but by no means the poorest (we see homeless peeing outside their window), the latter rich, but my no means the richest—they have bourgeois, not oligarch, money. The differences are extreme but smartly, for the story structure, not the most extreme. We watch the underclass Kims connive their way into the lives of the Parks. The Kims do this in the only credible way one can in such a society, by becoming the Parks’ servants.

We meet the Kims in scenes that show them surviving in a basement apartment by folding pizza boxes for compassionless small business people maybe one rung up the ladder from them. They are able to afford cell phones and computers, if not the wi-fi which they pirate. (This we see in the establishing shots in order to lead us to think they are the parasites–the capitalist rich are always parasites in the socialist view.) The Parks have bucks but display a parvenue lack of culture. Their home is elegant but its architectural lines and details were the creation of a famous architect and its former owner—the Parks didn’t create beauty, just purchased it. Like most bourgeois families, the Parks are easily satirized, and Parasite joins innumerable literary and filmic examples of such satire. Here the mother’s life revolves entirely around her overindulged children and her entitled lifestyle. She is simple, unskilled, and appears to have no real education and, we infer, gained her position through her beauty and her marriage. Her husband is a businessman, equally indulgent of her and the children.

To secure employment with the Parks, the Kims framed the Parks’ loyal and capable servants with false evidence of wrongdoing, and in the case of their housekeeper, with a manufactured case of TB. None of the Kims exhibits a moment of compassion, no guilty pause for rendering these people jobless or perhaps even homeless. For their part, the Parks are not only compassionless but lack even a basic sense of fairness—none of their servants is confronted with the charge or gets a hearing before being dismissed. The Parks’ concern is merely the most expedient way to send them packing.

The Kim son, the first to insinuate himself into the Park family, does so as a tutor for their 15-year-old daughter, gaining the job through the recommendation of his close friend, a university student taking a leave. The friend arranges this because he loves the Park daughter and is afraid another, less trustworthy guy, will move on her. The son generates false credentials to get the job, fakes sophistication by indiscriminately and empty-headedly describing real-world things as “metaphorical,” his judgment readily accepted by the vapid Mrs. Park. Once in, he immediately betrays his friend’s trust by hitting on, and exploiting the underage girl.

The Kims are entirely conscienceless, driven to survive, to advance themselves, fraudulently and at the expense of anyone in their way. They have no compassion for anyone, from the homeless guy outside their door, to those they’ve replaced, to a desperate man they encounter surviving in a bomb shelter deep under the Park home. I was reminded of “Viridiana” and Buñuel’s send-up of the notion of morality or propriety in the poor.

That bomb shelter, designed to ensure survival in the event of war with the North is, in a larger sense, a metaphor for the way the rich have lives that ensure their survival. It’s just one of the ways the rich are insulated from threats that the rest of the world must endure. Typhoons, earthquakes, floods, and drought barely inconvenience the wealthy even as disasters kill the poor and render them homeless. Bong illustrates this with a heavy rain that from the standpoint of the Parks is simply a lovely moment experienced at safe remove through their glass wall and an opportunity for their little boy to camp safely in the backyard under their watchful eyes. That same rain, Bong shows us, cutting to the Kims’ neighborhood, has produced a horrific flood that is wiping out peoples’ homes, carrying away their possessions. Metaphorical indeed.

In short, what Bong gives us is a perfect depiction of capitalist reality through a perfectly enacted story. At its conclusion there is a murderous attack on the Parks during a lawn party. Ideal endings, the trope goes, are supposed to be “surprising and inevitable.” There is a semi-surprising assault by the Kim father against the Park father. Whether it is inevitable, or even justified, is questionable. It is being taken by some viewers as an act of class warfare, but is it supportable as such?. Kim has been treated fairly, and respectfully, by Park. He has not been financially exploited beyond the broad sense in which everyone employed in a capitalist system may be said to be exploited by those above him, and treated far better than he was by the pizza vendors he was folding boxes for. Park’s only crime, such as it is, is to be put off by the odor of poverty, the odor he remembers from the days when he rode a subway, the odor on his driver Kim that, wafting into the back seat, he takes as an unacceptable crossing of the master-servant line. His murder is, in fact, triggered by Kim’s observing Park’s repulsion at the stench of the basement-dwelling man. Considering that the man probably hadn’t bathed in years and the repulsion evidence more of autonomic reflex than lack of empathy, is blame fair? Or, given what appears to be Bong’s ironic intention, is it fair to even ask?

We leave this very overhyped movie satisfied by the fine performances, the well-executed set pieces in the styles of the various genres, and by the sense that we’ve learned something about how the world operates–even if it’s no more than how unfeeling and opportunistic people are at every rung of the social ladder, and with no hope for anything different.

Thank you Don. How interesting that you’ve chosen to write about this picture. I actually hated it so I’m with you. Thank you for articulating what ultimately made it seem vapid to me. Ugly upon ugly it was…

And here it won so many awards, what does that mean?! (Folks are just confused by our world?!)

I watched it tonight. Kim’s assault on Park seems to begin with his unhappiness at being made to play an Indian. Park even has to remind him that he’s on the clock. Metaphorical?